Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy Restored

In critical circles, Satyajit Ray is a name held in the same high regard as fellow mid-century Art Cinema titans Bergman, Fellini, and Kurosawa. But the Indian director and his works have never quite passed into the general consciousness in the manner of his contemporaries. Although his films reliably show up on all-time best lists, especially his landmark “Apu Trilogy,” and especially the first of those films, Pather Panchali, he lingers on the sidelines in the U.S. A major factor in this neglect has been the accessibility and the condition of his films. For decades, the only available projection prints have been of poor quality, and home video issues looked washed out, scratchy, unfocused. Fortunately, the invaluable Criterion Collection has recently undertaken a massive restoration of the three Apu films, and new Digital Cinema Projection (DCP) “prints” are currently traveling across the country and will eventually be used for new Blu-ray and DVD releases. The results of the restoration are sensational; the films probably didn’t look this good on their initial release.

The Apu films are a classic Bildungsroman, following the central character from birth to manhood, through trials and triumphs. Pather Panchali (generally translated as “Song of the Little Road” and first shown in 1955) introduces Apu’s Brahmin family, living in poverty in a tiny Bengali village. His father, Harihar (Kanu Bannerjee), is a scholar and playwright, habitually unable to support his household. His strong-willed, sharp-tongued mother, Sarbajaya (Karuna Bannerjee), lives in a seemingly perpetual state of frustration. His older sister, Durga (Uma Das Gupta), is loving but mischievous, frequently enraging the better-off neighbors by stealing fruit from their orchard. And most memorably, his aged, toothless grandmother (actually, the exact relationship is never made clear), Indir Thakrun, totters around the family home, cackling and grumbling and constantly threatening to leave when she feels unrecognized or unappreciated. Chunibala Devi shamelessly steals the movie in an astonishing, vital performance in this role.

We witness Apu’s birth and watch him grow to about age seven through a series of picaresque episodes illustrating village life. Apu (Subir Banerjee) attends school in a dirt-floored, open-walled shelter that doubles as a shop. He and Durga play with other children and envy their relative prosperity. They explore the village and its surroundings, with much attention paid to local flora and fauna. In the film’s most famous sequence, they wander several miles from home in search of a reputed train track and are ecstatic to witness a train chugging past, which they run alongside. The father leaves in search of work, and the mother is forced to cope with starvation and a storm that destroys the family home. Indir dies, and then the teenage Durga dies from a fever, and when the father returns, the family packs up its remaining belongings and prepares to move to Benares (now Varanasi).

In the second film of the trilogy, Aparajito (The Unvanquished, released in 1957), Apu (now Pinaki Sen Gupta) and his family are in Benares where his father has established a small business leading prayers on the banks of the Ganges but soon sickens and dies. Apu’s mother finds steady work as a maid for a prosperous family, and she and Apu move back to the country. There, Apu attends a good school for the first time, and we watch him grow into a sensitive and intelligent teenager (Smaran Ghosal), fascinated by science, literature and foreign cultures. He earns a scholarship to university in Calcutta, and his mother experiences both pride and misgivings as he embarks upon a life that is far beyond her ken. Apu thrives as a college student but does not write or visit his mother as much as he should. When she dies, he performs her burial rites but then quickly returns to Calcutta to resume his studies, rather than taking up his uncle’s request to stay and become the village priest.

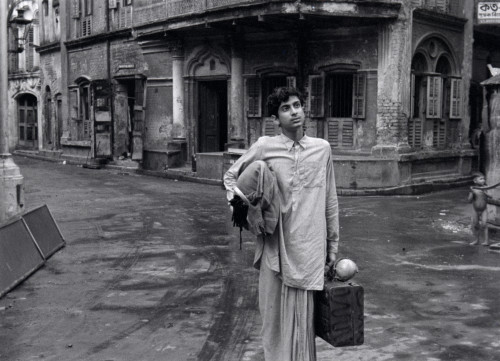

The final film, Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, released in 1959), finds Apu (now played by Ray regular Soumitra Chatterjee) as a young man, unsuccessfully looking for work. He joins his friend Pulu (Swapan Mukherjee) at a wedding in the country, and when the groom has a nervous breakdown and pulls out, Apu is convinced by Pulu and his wealthy family to save the day by marrying Aparna (Sharmila Tagore), the disgraced bride. Apu and Aparna return to Calcutta where she adjusts to her newly diminished circumstances, and the two grow to love each other. When Aparna dies in childbirth, Apu is thrown into a deep depression and abandons his baby son, leaving the child with his wife’s family. After wandering in despair for five years, Apu finally shakes his melancholy and accepts the responsibility of fathering his son.

For many Westerners, Ray’s films were their first exposure to Indian cinema, and the result was a skewed vision of that nation’s output. Even at home, Ray’s films were essentially art-house works, pitched not to the general public but to a cultural elite. The Indian popular cinema industry, massive even in the 1950s, churned out soap operas, musicals, action films, and adaptations of myths and legends, the vast majority of which never reached the West. The most popular film of Ray’s era was the epic melodrama Mother India (1957, directed by Mehboob Khan), often referred to as the Indian Gone with the Wind. Ray’s films, by contrast, were low budget, serenely paced, politically astute, and focused on the quotidian, not the exceptional. Whereas Mother India venerates a self-sacrificing mother and idealizes her relationship with her children, the Apu films complicate these roles; in fact, the rift between mother and son in Aparajito was shocking to Indian audiences of the day and was partly responsible for that film’s poor performance in its home country.

Ray began his professional life as a commercial artist in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and first engaged with the Apu story when he illustrated editions of its source material: two novels by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay. His interest in making a film version of the stories arose when he met the great French director Jean Renoir, in India to film The River. Ray helped Renoir scout locations, and the older director encouraged Ray to make a film of his own. Later, Ray spent half a year in London and went on a film-viewing binge. When he saw Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist masterpiece, Bicycle Thieves, he found the artistic model he had long sought. The humanist, objectivist influence of both Renoir and De Sica is profound in Ray’s work; in fact, his films owe much more to European Neorealism than to Indian film of the time. Bengali culture was in general quite open to cosmopolitan influence. Calcutta, as a major port and the capital of British India was, along with Bombay, among the most Westernized of the major Indian cities and was often regarded as the artistic and intellectual capital of the country, especially by the Bengalis themselves. But Ray was particularly cosmopolitan in outlook. Among the key Bengali art-film directors (including Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen), Ray is by far the least “Indian” in aesthetic terms.

For most of Pather Panchali’s cast and crew, this was their first film. Ray had little experience of rural life, let alone filmmaking; the cinematographer Subrata Mitra had never held a camera before; and the composer, Ravi Shankar, was not yet world famous, his encounter with the Beatles almost two decades in the future. Kanu Bannerjee and the two actresses playing the neighbors had film experience, and Karuna Bannerjee had stage experience, as did Uma Das Gupta. The boy cast as Apu was spotted in a yard in Calcutta and, according to Ray, proved to be a terrible actor although you’d never know it from watching the film, so expertly did Ray direct and then edit around him. Chunibala Devi, 82 years old at the time of filming, had been a prominent stage actress in Calcutta but had fallen into obscurity. Legend has it that Ray found her in a brothel (presumably not actually working there) and engaged her for this one last job, assuring her a place in film immortality. So convincing is she as the wizened, bent-over crone that it is difficult to tell how much of her performance is a brilliant physical feat and how much is simply her actual physical state at the time. She died shortly after the shoot.

Funding for the film initially came out of Ray’s own pocket. Ultimately, early footage was enough to convince the West Bengal state’s cultural office to finance the rest of the film. That process took most of the early 1950s and was conducted on a catch-as-catch-can basis. Every time Ray had some money and some free time, he and his cast and crew would adjourn to the village outside Calcutta where the shoot took place. There was little sense of what the audience or even the exhibition apparatus might be for a film like this. It was not until Ray showed footage to a very enthusiastic John Huston, in India for location scouting, that a path opened. Huston put Ray in touch with the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which ultimately gave Pather Panchali its world premiere. The second and third films were actually never planned. Each followed on the surprise success of its predecessor.

Pather Panchali shows signs of its minuscule budget. The sound can be crude, although it is used artfully, for example in the wrenching scene when Harihar learns of his daughter’s death and the diegetic sound drops out entirely, leaving only Shankar’s keening music to convey the father’s visible agony. But despite the budgetary constraints, the three Apu films, even Pather Panchali, are works of exceptional cinematic sophistication. Far from being crude, simple but “honest” ethnographic documents, they are intensely artful exercises in complex camera movement, powerful use of dramatic camera angles, and carefully rhythmic yet unobtrusive editing. In this, they are much like the Italian Neorealist films of De Sica (and Rossellini et al.) that so influenced Ray. As has long been noted, neorealism was never simply artless naturalism but was rather a carefully constructed style that utilized cinematic tools in the pursuit of the semblance of objectivity. Ray used this style as well as any director before or since. He and Mitra create images of magnificent beauty and suggestive power, images that are as constructed (in the best possible sense) as anything in a Hollywood film. The Apu films are full of sensual interplay of light and shadow. They fetishize silhouettes, reflections in bodies of water, displays of natural phenomena. In the penultimate scene of Pather Panchali, as the family packs to move, Apu finds a necklace that his now-dead sister had once stolen and hid on a high shelf. He takes it and throws it into a brackish pond near their home, and the camera pauses as the algae on the surface slowly closes over. “Aha,” we think, “a symbol for the memory of Durga being left behind as the family leaves.” But the algae does not quite completely cover the spot where the necklace landed; one small exposed circle remains, and the implication is that his sister’s tragic death has left a gap in Apu’s heart that cannot be covered over, which indeed is the case.

Over their six-hour running time, the Apu films present an extraordinarily vivid picture of life in the Bengali region of India in the early twentieth century, and although the central character is male, in many ways the sensibility and points of engagement in the films are feminine. The first two films are as much about Apu’s mother as they are about him. Sarbajaya is certainly the richest character in the first half of the saga: loving but severe, proud but humbled, ambitious for her children but conservative in her social expectations. In Pather Panchali, Ray defines and situates her directly between her two neighbors, one angelically kind and one nasty and contentious. Sarbajaya dominates the first film (in no small part thanks to Bannerjee’s superb performance), especially because the young Apu is essentially a passive character. Our first sight of him is a massive close-up of his eye, reluctantly opening as his sister wakes him. This image establishes his primary activity in the first film and a half: quietly watching.

Ray’s insight into the different stages of life is profound. Few films capture the childhood state of being an alert sponge as well as Pather Panchali. As Apu ages, Ray delicately traces the trembling promise of adolescence and the frightened bravado of young adulthood. Most poignantly, Ray beautifully limns the creeping obsolescence that encroaches upon the aging. Apu’s mother slowly loses her once-vivid presence in the films as time passes on, almost spiritually diminishing as her purposes in life disappear. The elderly Indir is virtually invisible to the rest of the characters, unless she is just in the way. In several striking sequences, she asks questions or demands attention and the others do not even acknowledge her, let alone respond. This abandonment works both ways, of course. The old are abandoned as they outlive their usefulness, but Apu is also abandoned, one by one, by his entire family and ultimately by his wife. Ray passes no judgment on any of these actions. His cinema is fundamentally impartial. The films set up an ongoing series of contrasts—city vs. country, old vs. young, tradition vs. innovation, rich vs. poor—but take no sides. And as in the films of his mentor Renoir, “everybody has their reasons”; no one in a Ray film is a villain.

Perhaps the chief theme of the Apu films is the onset of modernity in India. At first, the sense of “era” feels almost deliberately ambiguous. In Pather Panchali, Ray provides no indication of the year and, other than the brief appearance of the train and some vibrating telegraph polls (which delight and puzzle Apu and Durga), the setting might almost be medieval, so backward is the village. One senses that the residents live much as they have for centuries. Then, as the family arrives in Benares at the beginning of Aparajito, a title on the screen fixes the year as 1920. In this film, Apu encounters electricity for the first time (his room in Calcutta is outfitted with a light bulb, he delightedly writes to his mother). The trains that had seemed like magical conveyances from the future in the first film are now parts of Apu’s daily life. They take him from the country to the city and back again, and almost supply him with a means of suicide at the darkest moment in Apur Sansar. Interestingly, the British Raj is virtually absent in these films. Portraits of the British monarchs on the coins are the only physical reminders that the country is under occupation. As Apu becomes more educated, English words increasingly pepper his vocabulary. And in Apur Sansar, his room is decorated with thumbtacked photos of the kind of “Great Men” a young scholar of the time might have admired: Einstein, Shaw, and H. G. Wells.

Over the course of the three films we also see forms of entertainment changing. In Pather Panchali, Apu and his family enjoy village holiday rituals. In Aparajito, Apu attends a play while at school. And in Apur Sansar, he and his wife go to the movies, watching a fairly ludicrous adaptation of an ancient myth (Ray’s tongue firmly planted in cheek, no doubt). But the onset of modernity is not just a matter of inventions and technology. The films also trace profound changes in social currency, although always in a quiet, undogmatic fashion. The first two films contain numerous scenes of a man eating from his thali as a woman quietly sits and fans him; Apur Sansar shows that same scenario between Apu and Aparna and then immediately, pointedly, and cheekily reverses it as Apu solicitously fans Aparna while she eats her meal. The physical manifestations of the relationship between Apu and his parents in the first film are essentially transactional. He is fed, bathed, clothed, but not really spoken to or engaged. At the end of the third film, we sense that the relationship between Apu and his son will be different. When the child, who has been raised by his grandparents in Apu’s absence, asks his father just who he is, Apu replies, “I am your friend.”

Early critics of the films noted their tragic view of life, but while the films are indeed full of death, I think that their worldview is not tragic but rather multifarious. The first two films each include the deaths of two major characters, but they also encompass joy, tenderness, wonder, and humor, not to mention fury and sorrow. Ray incorporates all of these disparate emotions with expert, organic grace and finds contour in what is technically a shapeless, anarchic life story. The third film contains only one major death, although a second, Apu’s potential suicide, is introduced as a possibility. But instead, the cycle culminates in a great apotheosis as Apu decides to reject the abandonment that has characterized his life so far and to rejoin the community with his once-estranged little son in his arms. The series of incidents that begins with Apu’s birth in Pather Panchali ends with his rebirth after returning from a death-like despair in Apur Sansar. The project of the third film’s climax is actually a part of the greater project of the entire cycle: a trajectory on the part of Apu from passivity to engagement with life.

The experience of watching the Apu films today cannot possibly be what it was sixty years ago. No style is so transparent that it does not date as time passes, and that is as true for naturalism as it is for expressionistic art, probably even more so. For example, “Method” acting, once viewed as so realistic that it was like the conveyance of pure, unmediated behavior, now seems intensely, if wonderfully, mannered. The great Italian Neorealist films of the 1940s (Bicycle Thieves, Open City, Shoeshine), while still immensely powerful, have dated as well. Neorealist narrative owes a great deal to melodrama, especially in its foregrounding of intense episodes of suffering and joy at the expense of the flatter affect of daily life. Today’s “Slow Cinema,” with its celebration of the poetry of the commonplace, makes Ray’s early cinema seem overly determined, not just in its melodrama but in its incessant use of the Pathetic Fallacy (the heavens seem to shake and weep anytime someone dies) and in its occasional overly choreographed moments of beauty, such as the gorgeous explosion of fireflies that Apu’s mother sees in her garden right before she dies. At the same time, what had apparently seemed a rather listless sense of pacing in the 1950s now seems quite average, at least by current art-film standards. Pather Panchali has moments in which its action grinds to a halt, but the recompense is usually a moment of poetic beauty, such as the long sequence wherein the ancient Indir sings a mournful folk song while sitting outside in the evening, the camera slowly circling and closing in on her endlessly expressive form. Because of these frequent “moments in time” and its lack of formal narrative, Pather Panchali is still seen as the “purest” film of the trilogy, the one that most often represents the whole, its synecdoche (a word that is amusingly parsed in a classroom scene in Aparajito).

In fact, on the initial release, a subset of critics who had fallen in love with Pather Panchali felt that the second and especially the third film had betrayed the first’s radically loose structure in favor of a slicker, more conventional dramaturgy. Pather Panchali is certainly lacking in the usual trappings of fiction: conflicts that build and climax, protagonists who move toward epiphanic revelations. And Aparajito and Apur Sansar certainly have more conventional arcs, more clearly delineated structures. But these critics underrate the second and third films. Pather Panchali lacks cause-and-effect plot progression because it is a film entirely seen through a child’s eyes. Its fragmented narrative, its conflicting and sometimes confusing elongation and condensation of time, its focus on quotidian affairs—all of these are clearly strategies by Ray to re-create the inner life of a preadolescent. As we age, we begin to ascribe more motivation, more structure to the events of our lives, and thus Aparajito and, ultimately, Apur Sansar become more motivated, more structured. The pace of the films changes along with the pace of life as experienced by its protagonist. As we get older, of course, everything begins to move more quickly. Pather Panchali views time through the lens of childhood when a single summer can feel like an epoch.

Initial critical response to the Apu films in the West, while certainly positive, was unsurprisingly saturated with the orientalist and paternalistic attitudes of the era. Many reviews treated the films as quasi- documentary looks at the heroic struggle against the vicissitudes of poverty. Most reviews also noted the laconic pacing and attributed it to a lack of American know-how rather than a conscious aesthetic choice. The well-meaning but reliably obtuse Bosley Crowther, chief film critic of the New York Times, condescendingly approved of Pather Panchali’s “touching indication that poverty does not always nullify love and that even the most afflicted people can find some modest pleasures in their worlds” but assured his readers that, “any picture as loose in structure or as listless in tempo as this one is would barely pass as a ‘rough cut’ with the editors in Hollywood.” Crowther was a political liberal but an aesthetic conservative, and while his review was generally positive, it might have been a business-killer had not positive word of mouth spread. Pather Panchali was a big hit on its initial commercial New York release in 1958, playing for eight months at the Fifth Avenue Cinema. By the time the second and third films were released, Crowther had jumped on the bandwagon and raved that Ray “demonstrates that he is a master of a complex craft and style.” What was most galling about the condescension from Crowther and many other critics was that the films themselves have not a lot of it. Their depiction of poverty has none of the “triumph of the little people” sentiment that mars so many Hollywood representations of the poor.

No doubt this compartmentalizing of Ray was strengthened by the generally poor quality of the prints that circulated right from the initial release. Ray died in 1992 (after having received an honorary Academy Award the previous year) and, almost immediately, attempts to preserve his films were put into action. The Merchant/Ivory Foundation created new prints of the Apu Trilogy and six other major Ray films in 1995 and re-released them commercially, but the source material was inherently flawed. In 1993, the original negatives of the Trilogy had been transferred to London, but in July of that year an explosion (common in vaults containing highly flammable nitrate film) sparked a disastrous fire, severely damaging the precious original documents. The burned and melted negatives were then stored in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ archives where they sat for twenty years. Then the Criterion Collection, planning a new home video release of the films, went searching for the best possible source material and unearthed these negatives, discovering that about half of them were salvageable. The usable frames were rehydrated, repaired and scanned in Ultra-High Definition. Bringing in materials from other early-generation prints and doing restoration work on them as well, the films were essentially put back together frame by frame. In the final analysis, about 40% of the restored Pather Panchali and 60% of Aparajito comes from the original negatives. Unfortunately, none of Apur Sansar’s negative was salvageable, so Criterion turned to a fine grain master and a safety dupe negative, and the results are almost as good as the first two films. The new digital prints are now making the rounds of the nation’s revival houses, having sold out, as of this writing, three solid weeks at New York’s Film Forum.

The restoration accomplishes exactly what it needs to, which is that it reveals the films’ artistry in deeper and clearer ways. Previous viewings of the Apu films have left me with the impression that they were rough and threadbare, though intense and poetic. These new mintings make it clear that Ray’s vision was as sophisticated as any world-class filmmaker of his era, his eye for image, light and space as telling as Bergman’s, Ozu’s or Dreyer’s. As an added benefit, the newly redone subtitles clarify and characterize the films and their protagonists in more specific and extensive ways than before. (Poorly translated, hard-to-read subtitles were often the bane of mid-century foreign films, especially black-and-white ones). Film, especially nitrate film, is extraordinarily fragile. When it has been improperly stored, it can be virtually impossible to work with, disintegrating when unspooled. The artisans at Criterion and its partners are true cultural heroes, preserving invaluable works of art for future generations that otherwise might literally disappear. The intersection of art and commerce is not always pure, but the Criterion Collection is an absolute good in the cultural world.

With the Apu Trilogy, Ray entered the world of cinema as a fully formed artist. And his subsequent, illustrious career proved that the Apu films were no fluke. His influence has not been powerful in India, but in the West he has cast a long shadow on subsequent filmmakers, despite his relative lack of awareness among the general public. Richard Linklater’s masterpiece, Boyhood, released last year, is just one of hundreds of films that owe a deep debt to Ray. His art perfectly illustrates the power of the universal when it derives from the particular. Ray filmed a very specific story set in a very specific place, eschewing artificial attempts to universalize the setting or the films’ vocabulary, and the result has spoken eloquently to the entire world.[1]

[1]The author wishes to thank Drs. Erin Mee and Shanker Satyanath for their input into this review.